FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler is circulating a regulatory proposal to his fellow commissioners that he hopes will create additional competition for pay-TV set-top boxes. This comes after a handful of technology companies advanced their own regulatory proposal, often referred to as AllVid. We do not know the full details of what is in Chairman Wheeler’s draft, of course, but we do know what AllVid proponents asked him to do. And it is troubling.

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler is circulating a regulatory proposal to his fellow commissioners that he hopes will create additional competition for pay-TV set-top boxes. This comes after a handful of technology companies advanced their own regulatory proposal, often referred to as AllVid. We do not know the full details of what is in Chairman Wheeler’s draft, of course, but we do know what AllVid proponents asked him to do. And it is troubling.

Supporters of AllVid claim critics are just defending set-top box revenues. That is certainly not the MPAA’s motivation, as content creators do not receive those revenues. What concerns content creators is that AllVid isn’t really about helping viewers access content they have paid for; it’s about companies profiting from content they haven’t paid for.

What AllVid proponents are actually seeking is federal rules to siphon pay-TV content and repackage select portions of it for their own commercial exploitation through fees, advertising, or data collection, and without having to enter into agreements with the creators like others in the marketplace must do. This amounts to government-compelled speech—striking at the core of First Amendment and copyright law—and would undermine programmers’ ability to develop and make available high-quality content. Such a technology mandate could also increase content theft by weakening security, making it easier for piracy-laden “black boxes” to connect to legitimate services, and by prominently displaying stolen content from the Internet alongside authorized content.AllVid imposes these harms on content creators with little need—and even fewer benefits to viewers.AllVid would not provide viewers access to any additional content that isn’t already available over the pay-TV and broadband services already coming into their homes. And contrary to its proponents’ claims, AllVid would stifle competition rather than promote it by giving certain players an unfair regulatory advantage over those that are appropriately entering into agreements with creators, as well as reducing proponents’ incentive to create original content or deploy their own facilities-based services.

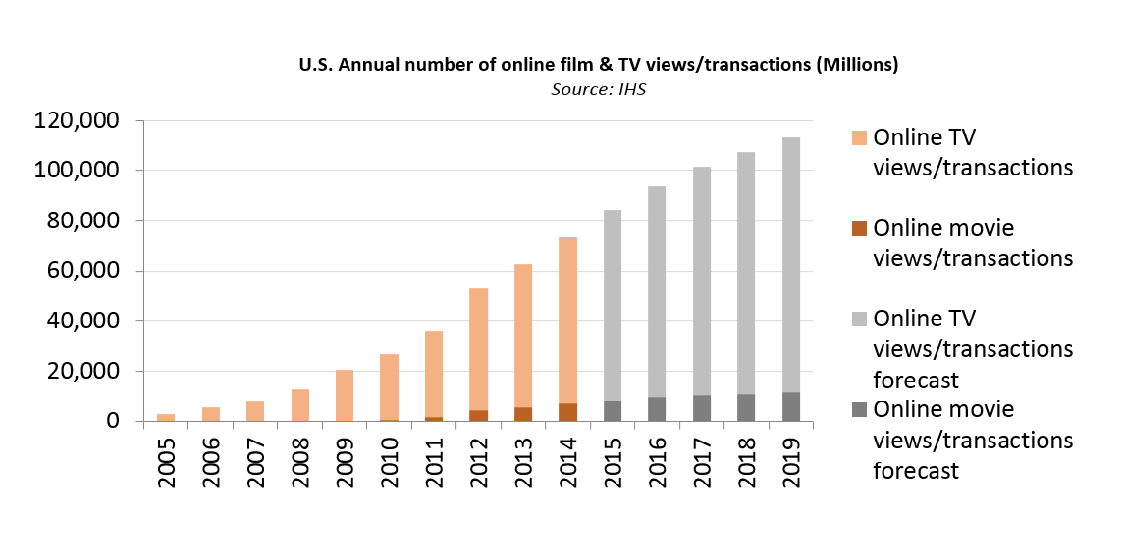

Some viewers wish to “cut the cord,” but AllVid won’t help them because it only works so long as viewers are subscribing to a pay-TV provider. What is helping these viewers is the extraordinary number of movies and television shows content creators are making available online. Audiences are already watching tens of billions of television episodes and movies per year that content creators offer directly over their own Internet applications, as well as through over-the-top services from companies such as Amazon, Hulu, Netflix, Sony, Sling TV, and Microsoft. Some of these OTT providers are also financing their own original programming. To help viewers navigate among all the choices, the MPAA created WhereToWatch.com, a free search site that enables fans to locate television shows and films by title, actor, or director and click through to lawful online sources, as well as see show times and buy tickets for movies still in theaters. Hollywood usually loves a sequel, unless, of course, the original was a flop. The FCC declined to pursue the AllVid mandate in 2010 because of technological, policy, and legal problems with the proposal. In light of all the creativity and innovation that has occurred in the video marketplace since then—and for the sake of the creativity and innovation yet to come—we hope the agency will decline to do so again.